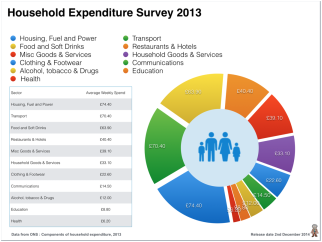

Few can remember the 1930’s but many love to talk about. It is as if they were there, at the time, on the bread line, waiting for the soup kitchen to open. For many, falling prices recalls the history of the great depression. A period of falling prices - a result of demand deflation. A virtuous circle of twenties excess, morphed into a peccant process of impecunious imposition. Prices fall, demand collapses, the economy implodes. Will consumers postpone purchase decisions? Some believe, that when prices are falling, consumers will delay purchase decisions. Demand falls, business suffers. A collapse in sales means that investment decisions are postponed. The fall in demand leads to business layoffs. Business layoffs, lead to higher unemployment. Higher unemployment leads to lower incomes. Lower incomes lead to a fall in effective demand and before we know it, we are back on the bread line, scrabbling for crumbs. Keynes spoke of the Liquidity Trap. Alvin Hansen developed the term “secular stagnation”. describing what he feared was the fate of the American economy following the Great Depression of the early 1930s. A lack of technical innovation to stimulate growth and demand in a slowing economy would lead to a permanent stasis of low and declining economic activity, he said. Larry Summers, supported by Paul Krugman and others resurrected the theory in 2014, suggesting advanced economies might be suffering from “secular stagnation” post the 2008 crash. A lack of demand, would lead to low growth, low growth would lead to secular stagnation and we would enter into the Keynesian liquidity trap. Strange - as this year, growth in the USA returns to trend and the world economy is set to grow by over 3% this year. Hansen’s forebodings were proved to be quite wrong in 1938. Those fearing secular stagnation, lower prices and a bout of deflation will be equally derived of the downside in 2015. Cost push or demand pull? Before monetarism became fashionable, we were taught to distinguish between inflation as a function of cost push or demand pull. Conversely, deflation is a function of cost push down or the lack of effective demand. Retail prices in the current round are affected by lower oil and energy costs together with lower commodity and food prices. Good deflation results from lower costs - oil, energy, transport, utilities, food and commodities. Bad deflation results from a lack of domestic demand and an immediate threat to output. The lack of domestic demand in Euroland is rather more complex and concerning but the lack of effective demand is less of an issue in the rest of the world. For monetarists, those who would believe that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon have been particularly disappointed by the lack of inflation post QE and life on Planet ZIRP with interest rates set at the zero bound. At present, inflation is always and everywhere an international phenomenon, determined by the relatively low growth of world trade and a commodity cycle, including oil, in an over supply phase. Will consumers postpone purchases if prices are falling? Will consumers postpone purchases if prices are falling? Not really. Analysis of household spending in the UK confirms almost 80% of spending is non discretionary. Spending on housing, fuel, utilities, transport, food, drink, alcohol, drugs, tobacco, clothing, footwear, education, communications and health are unlikely to be affected by falling prices. The so called elasticity of inter temporal substitution as a function of negative prices is extremely low in many sectors. In household goods, electricals, mobile phones and computing for example, hedonic price adjustments have meant prices have been falling in real times for decades. Clothing and footwear prices are15% lower than 2000. White goods and electrical down 50% over the last decade. Highly discretionary non essential luxury goods, may lead to a price postponement. But if I thought my new Bentley would cost 2% less next year would I really wait? Car sales have been booming in 2014 in the UK but easy finance and payment plans have meant no significant capital outlay is required. Immediate gratification is a higher motivation to expenditure the variations in the savings ratio and the life cycle hypothesis. The frog in the saucepan, the explorer in the stew pot ... When we talk of the dangers of low inflation, we worry of low inflation, slowly rising, out of control, leading to hyper inflation. Low inflation is like the frog in the saucepan or the explorer in the cannibal’s stew pot. Happy at first as the temperature slowly rises, discomforted significantly, as boiling point nears. Rising inflation, raises fears of vast quantities of devalued currency, moving around in wheelbarrows, as with the period of hyperinflation in the Weimar republic. Lower prices and a bout of deflation are not a threat to consumer spending in the short term. Quite the opposite, as the kick to real income growth takes effect, spending may increase. But left untended deflation is a problem. The frog in the saucepan hops out into the cold. Cold turns to light frost. Light frost to freezing, somnolence and hypothermia ensues. Hibernation or death is the option. Lower prices in housing for example would be a major problem. If houses will be cheaper in a years time and even ten years time. Who would want to borrow against a depreciating asset? The housing market would suffer. The buy to let market would be a modest beneficiary but the damage to the construction sector would be intense. So a short, small bout of deflation may not be a bad thing. But a prolonged period of falling prices would mean the frog is out of the saucepan, falling asleep along the side of the road. We should welcome but be wary of negative inflation rates.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The Saturday EconomistAuthorJohn Ashcroft publishes the Saturday Economist. Join the mailing list for updates on the UK and World Economy. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

| The Saturday Economist |

The material is based upon information which we consider to be reliable but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. We accept no liability for errors, or omissions of opinion or fact. In particular, no reliance should be placed on the comments on trends in financial markets. The presentation should not be construed as the giving of investment advice.

|

The Saturday Economist, weekly updates on the UK economy.

Sign Up Now! Stay Up To Date! | Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed