|

Writing in today’s Daily Telegraph Roger Bootle makes the point that economics is too important to be left in the care of academics. The emphasis on mathematics and econometrics at the expense of economic history and pragmatic interpretation of events is evident. “Pick up the leading journals today and even many economists cannot understand the titles, never mind the articles. Open the pages, littered with algebra, and you could be forgiven for thinking that you were looking at a musical score. The mathematicians have taken over.”

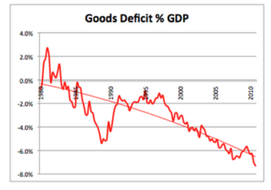

“Students of economics today are force-fed theoretical models of startling banality and irrelevance, leavened only by doses of econometric techniques of dubious validity and near-zero intellectual interest. Typically, they complete their course knowing nothing about the British economy and untrained in how to think.” I do like Roger Bootle. I once went on a course to understand GARCH modelling. This is a modelling technique involving Gaussian or general autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. I didn’t understand a word as the lecturer began to chalk obscure hieroglyphics onto a blackboard from 9:00 am in the morning. There were only six of us in the room and was feeling more than a little overwhelmed. As time moved on 11:30 in fact, the lecturer realised he had made a mistake in the chain process at around ten minutes passed ten and a full hour and ten minutes were wiped off the board. We broke for coffee and I didn’t go back. If you read the minutes of the Bank of England Monetary Policy committee for last month you begin to think that RB has a good point. The Bank of England is puzzled that theory isn’t working. A depreciation of sterling according should lead to an improvement in the Balance of Payments. Exports are cheaper and imports are more expensive. There should be a reduction in import volumes but the bank noted : “It was puzzling that import growth had remained so robust, despite the substantial depreciation of sterling. It was possible that domestic substitutes for some imported goods and services were not available. It was also possible that UK firms in some industries lacked the plant or capacity to expand production rapidly in response to the past depreciation of sterling and it would take time for them to install it." Hello! It’s a wake up call for the Bank of England. The Bank has over two hundred economists educated to Masters or PhD standard. They produce much research and analytical papers. Two of my favourites from last year are : “How non Gaussian shocks affect risk premia in non-linear DSGE models”. (No. 417) and “An efficient method of computing higher order bond price perturbation approximations.” (no 416). Very helpful to policy makers everywhere, I am sure. Someone should commission a paper and send it to the MPC, on why depreciation has never worked, be it 1931, 1947, 1967 or 1992. Peter Spencer of the ITEM club points out the manufacturing has been in decline since the 90’s. I presume he meant the 1890’s. In 2011 there is little manufacturing capacity in the UK and this is likely to remain the case. There will be no rebalancing of the economy towards net trade surplus. In 1983 the UK went into deficit in manufactured goods following the Howe Thatcher pogrom. The trend decline is getting worse not better. Only in one manufacturing sector, chemicals does the UK trade at a surplus the rest is in serial deficit. The Bank seems to think that in pubs around the UK discussions are taking place about the merits of open hearth steel making versus Bessemer and the electric arc furnace. Resurrection of tube making facilities using the pilger process is also on the agenda presumably but where to buy the equipment? Back to the darts with a pint and a packet of pork scratchings the only option. Import substitution - buy real ale. Devaluation isn’t working but then it never did.

0 Comments

In 1931, the deficit on balance of trade in goods and services amounted to -2% of GDP. The import bill for food, beverages and tobacco amounted to 8.6% of GDP. Add in the raw materials bill, and a manufacturing surplus of just £72 million could do little to offset the 12.3% GDP bill for essential imports in food and basic commodities. Invisible earnings, which would normally finance the import bills had been hit by a fall in revenues particularly shipping revenues as world trade collapsed.The UK government faced a crisis which was to lead to Sterling leaving the Gold standard and a devaluation from the level of $4.86 to the dollar. Eat less and export more was the call to remedy the problem. In 1948, A net trade deficit of just under 2% precipitated the devaluation of Sterling from $4.20 to $2.80. As always the mantra, eat less, export more was prevalent. A food bill of some £450 million amounted to just under 4% of GDP. Including raw materials, the total amounted to 7% of GDP. The UK was struggling to finance the deficit either in terms of manufacturing surplus or invisibles surplus. By 1950, according to Coutts and Rawthorn, the UK was a great industrial power with more than a third of its labour force employed in the manufacturing sector. There was a trade surplus in manufactured goods equal to 10% of GDP and the country was a net exporter of energy. All appeared to be well, the overall deficit was less than one half of one per cent. In 1967, seventeen years the Labour government was obliged to run cap in hand to the IMF as a result of a balance of payments crisis. This lead to a further devaluation of the currency. The actual balance of payments numbers were inconsequential, confidence was everything and the Wilson government offered little. The pound in your pocket was unaffected as the devaluation from $2.80 to $2.40 was to unfold. The run on the pound had been triggered by a balance of payments deficit less than 1% of GDP. Forty three years later in 2010, the UK had a deficit on food of just 1.2% of GDP, add in the bill for raw materials and the deficit amounted to less than 1.5%. Yet the overall deficit on trade in goods amounted to 6.7% of GDP. Since 1983, the UK has been running a persistent deficit on manufactured goods which has compounded the trade deficit problem. In 2010, the trade deficit on manufactured goods amounted to -4.6% of GDP. The surplus on invisible account could not cover the trade deficit. The overall deficit in goods and services was -3.3% of GDP. In Q4 alone the deficit was -4% of GDP. The situation is worse than 1931, 1948 and 1967. How did the UK get into this situation? Our research paper “Forty years of UK Trade” analyses the deterioration in the UK Balance of Payments position. For those expecting to see the rebalancing of the economy towards net export growth following the devaluation of the currency once again, it should be an interesting read. The UK needs a strong banking and financial services sector to offset the manufacturing deficit. This is no time to be bashing the banks. |

AuthorDr John Ashcroft ArchivesCategories |

| The Saturday Economist |

The material is based upon information which we consider to be reliable but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. We accept no liability for errors, or omissions of opinion or fact. In particular, no reliance should be placed on the comments on trends in financial markets. The presentation should not be construed as the giving of investment advice.

|

The Saturday Economist, weekly updates on the UK economy.

Sign Up Now! Stay Up To Date! | Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed